Recursion

What is recursion

The best one liner that I’ve come across to explain recursion is this:

“Recursion is when a function calls itself until it doesn’t.”

~ mpj on Fun, Fun, Function

How to use recursion

One of the classic examples of illustrating recursion is by using it to determine the Nth value within the Fibonacci sequence.

What is the Fibonacci Sequence

The Fibonacci sequence is a series of numbers, where each number is the sum of the two preceding numbers in the series.

Here’s the first 12 numbers of the Fibonacci sequence:

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144A few things to note

- Sometimes the Fibonacci sequence is depicted starting with 0, here we don’t, but it really doesn’t matter, as this article is about understanding recursion.

- The first two values in the Fibonacci sequence are always 1, and since you can’t get the sum of the

two preceding numbersof positions 1 and 2 in the sequence, these are considered given. - Take a look at 2 (in position 3), however, and you’ll see that the two preceding numbers are 1 and 1. Add them together and you get two.

- Same thing for 5 with 3 and 2, and so on…

Contriving a recursive solution for Fibonacci

Let’s start with a problem statement:

Given a number, return the value from the Fibonacci sequence at that position.

With that in mind we can envision:

- receiving

1and returning 1. - receiving

2and returning 1. - receiving

3and returning 2. - receiving

4and returning 3. - receiving

5and returning 5. - etc…

The anatomy of a recursive function

Base Cases

Remember: Recursive functions are functions that call themselves until they don’t.

Let’s talk about “until they don’t”.

If we look at a while loop like the below, we can probably see that it will run forever:

while (true) {

console.log("Help, I'm in an infinite loop!");

}

There is nothing telling the above loop to stop what it’s doing.

Now look at this example:

let counter = 0;

while (counter < 10) {

console.log(`Counter is: ${counter}`);

counter++;

}

console.log("And we're done.");

return counter;

- We enter the while loop when

counteris less than 10. - We print a message.

- We increment

counter - When

counterhits 10, we leave the while loop. - We print a final message.

- We return

counter

This is the basic premise behind, “until it doesn’t”; however, when we are talking in terms of a recursive function, we use the phrase base case.

A base case tells a recursive function to stop calling itself (usually by returning something).

How a function calls itself

Take a look at this function:

function fib(n) {

console.log("We are in an infinite loop!");

return fib(n);

}

While can see that the function actually returns itself, this is a really bad function for a couple key reasons.

- There is no base case, telling the function not to call itself anymore.

- The arguments in the returned function do not change.

Both of these problems cause the function to run in an infinite loop.

☝️ Remember this!

- You always need one or more base cases that will allow the function to stop calling itself.

- When recursing back into a function, the arguments must change in such a way that a base case will eventually be met, allowing the function to stop calling itself.

Let’s fix these so that this recursive function is similar to the while loop example from above.

function fib(n, counter = 0) {

if (counter === 10) {

console.log("Base case has been met.");

return n;

}

console.log("We are in a recursive loop!");

return fib(n, counter++);

}

While not terribly exciting, since we’re always just returning n, we are at least not stuck in an infinite loop.

☝️ Note that the

counterparameter is set with an initial value of 0, using default parameters, which is a new feature of JavaScript ECMAScript 2015 (a.k.a. ES6).

Why is works is due to the following:

- The counter is set to 0.

- If the counter is < 10, we call the fib function again with the new argument of

counter++. - We hit the base case once counter = 10, and we return

n, which causes us to leave the function (i.e. “it doesn’t call itself anymore”).

So let’s apply this pattern to the Fibonacci sequence.

Solution

We know from the definition that the value of any given number, n, in the Fibonacci sequence is the sum of the two proceeding numbers.

So let’s think about that for a moment:

To get the Fibonacci number at position n, we need to know the value of the Fibonacci numbers at positions n-1 and n-2.

value of Fibonacci at n = value of Fibonacci at n-1 + value of Fibonacci at n-2😱 If you feel your head imploding at this point, that’s perfectly normal. Read the above line three times aloud and look at the below:

function fib(n) {

return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2);

}

We’re getting there, but the above function is incorrect due to one key missing ingredient: there is no base case! This means, yep, an infinite loop.

But before we get to the base case, let’s understand what the above function is actually trying to do.

- It receives

nas a value. - As we want to determine the Fibonacci number at position

n, we need to know the Fibonacci numbers at positionsn-1andn-2. - To do this, the function calls itself (twice) to determine what those values are.

Okay, so how to we stop it

If we recall, the first two numbers in the Fibonacci sequence are always 1. Therefore, we can write a base case around this.

if (n <= 2) return 1;

With this: if n is 1 or 2, the base case is met and the function will return 1.

☝️ Take note that we are considering positions in the Fibonacci sequence. We are not considering positions in an array, so don’t think as if we are trying to access values with a zero-based index.

Putting it all together

function fib(n) {

if (n <= 2) return 1;

return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2);

}

What’s happening here

Assuming we call the function with fib(3), here’s how the function works

- It checks if

nis <= 2, which it is not - It returns

fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2), which is actually calling itself twice with different arguments, trying to get the two previous Fibonacci numbers in the sequence behindn. - Each of these are processed in turn.

- As the function tries to resolve

fib(n - 1), the parameternis now2, because fib was called with the argumentn - 1, or3 - 1. 👈 read that again - With

n = 2the function will return 1, as thebase caseis satisfied.

🔥 At this point, we now know something!

value of Fibonacci at 3 = 🔥1🔥 + value of Fibonacci at n-2- The function then proceeds to try and resolve

fib(n - 2) - As the function tries to resolve

fib(n - 2), the parameternis now1, because fib was called with the argumentn - 2, or3 - 2. 💡 Are things starting to click now? - With

n = 1the function will return 1, as thebase caseis satisfied.

🔥 And now we know two things, and we have the solution!

value of Fibonacci at 3 = 🔥1🔥 + 🔥1🔥 = 2I used fib(3), as it’s the shortest explanation; however, as we try to find Fibonacci numbers at higher positions of n, the process is the same but the fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2)s will continue to stack up in memory as the function works its way toward the solution.

Is Using Recursion a Good Idea

Using recursive functions to solve problems, while seemingly elegant, is often not the best approach.

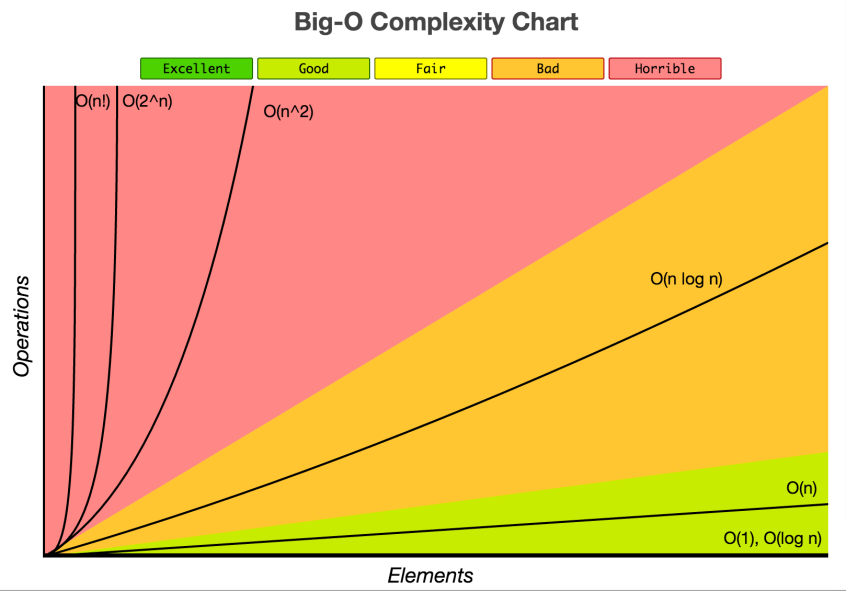

The main reason for this is that complexity (both time and space) for recursive solutions is usually pretty bad. In fact, in can be horrible 👹

For example, the above solution would be considered to have a Big-O time complexity of O(2^n).

Big-O Time Complexity

Why is it horrible

Every time the function runs this line of code:

return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2);

Memory is allocated (on the computer’s call stack) toward resolving any fib(n) where n is greater than 2 (more on “greater than two” below).

The biggest potential problem with this is that there is a finite number of things that you can add to the call stack, and if you pass a large enough number as n, you will exceed the limit of the call stack resulting in a stack overflow, which basically crashes the program.

The other problem with this approach is that it is inefficient, in that every time the that return line runs, we have to calculate it, often recalculating the same thing more than once.

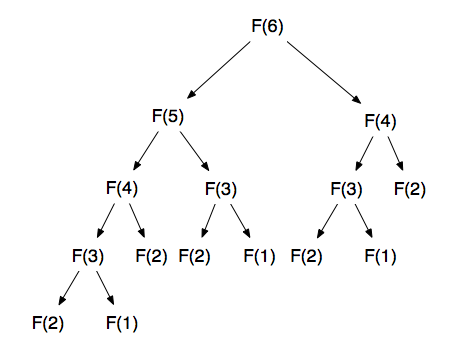

For example, take a look at the following representation of how fib(6) is derived:

fib(6)

Look how many times F(3), or fib(3), is called: 3 times.

☝️ Note that fib(1) and fib(2) are not of great concern, because we have basically hard coded the result of these into the function; however, when seeking ever larger fib(n)’s greater than 2, the repeated calculations become significant.

To address this, we can leverage the concept of Dynamic Programming toward making this function much more efficient.

Dynamic Programming Approaches

Memoization

function fib(n, memo = []) {

if (memo[n]) return memo[n];

if (n <= 2) return 1;

let res = fib(n - 1, memo) + fib(n - 2, memo);

memo[n] = res;

return res;

}

Tabulation

function fib(n) {

const fibNumbers = [0, 1, 1];

if (n <= 2) return 1;

for (let i = 3; i <= n; i++) {

fibNumbers[i] = fibNumbers[i - 1] + fibNumbers[i - 2];

}

return fibNumbers;

}